- September 16, 2014

- Posted by: BlueSkies

- Categories: Climate, Environmental, Hazard Mitigation

Water Scarcity

Fresh water is among the earth’s most precious resources – we drink it, cook with it, bathe in it, farm with it, and use it in the generation of much of the world’s electricity. It is fundamental not only to life, but to our way of life.

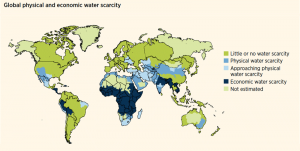

Yet water availability is not assured for billions of people across the planet, and research has indicated that in the near future, an even larger percentage of people will likely face water scarcity.

The reasons behind the projected increase in water scarcity can be boiled down to supply and demand.

Supply

The supply of fresh water comes from precipitation and is stored in lakes, rivers, aquifers, and snowpack. Weather obviously affects the water supply from season to season and from year to year, but over the long term, climate is the main driver.

When the climate is in a relatively steady state (as it was for about the past 12,000 years as humanity developed agriculture, civilization, and technology), so too is water availability. Sure, droughts and very wet periods occur, but over decades and centuries, it tends to even out.

However, when the climate is rapidly changing (as it is now), water availability becomes less certain. Precipitation patterns shift and so too do the locations and levels of lakes and rivers, aquifers and snowpacks. The sources we have depended on for water become undependable.

That’s what we’re facing now. The supply of fresh water is shifting – increasing in some places and decreasing in others. Unfortunately for us, many of the regions that are expected to see a decrease in total water availability are also heavily populated.

Demand

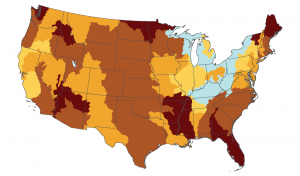

And here is where supply predictably meets demand: people use water. Primarily, we use it to grow food and to produce electricity. In the US, these two uses account for over 75% of total water withdrawals.

As the global population grows and becomes more industrialized, we have more mouths to feed and more high-tech lifestyles to power. If we continue with business as usual, we could face a direct conflict between agriculture, electricity generation, and other water uses by 2040. We could literally use up all of the available water in the system.

Judicious and mindful use of water (i.e. not being blatantly wasteful) and adoption of more water-efficient farming practices can go a long way towards conserving water resources (demand side), while the energy sector offers opportunities for a “twofer” — both reducing water use (demand) as well as mitigating climatic changes that threaten to disrupt water availability (supply).

All thermoelectric power systems (like the combustion of coal or natural gas to produce steam that drives turbine generators) require inputs of water, both to create the steam and often to cool it. Meanwhile, if the power plant relies on a hydrocarbon fuel, it’s also emitting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Solutions

Solar and wind power are familiar and growing alternatives to traditional thermoelectric electricity generation methods, and they offer the twin benefits of significantly reduced water use and dramatically reduced greenhouse gas emissions. For people living in developed regions that can provide the supporting infrastructure and dependable maintenance that solar and wind systems typically require, these alternative energy solutions are very promising.

But for people living in less developed or simply less accessible regions, portable gasoline- or propane-powered generators are often their only option — although perhaps not for much longer. Andrew Kazantsev and his team of Russian scientists have reportedly developed a device that collects atmospheric moisture and channels it down to the ground where it can be used for both drinking water and electricity generation.

The device, called Air HES looks like a small dirigible (aerostat) with a fine mesh hanging below it. The aerostat rises to the mid-levels of the atmosphere, where water vapor and water droplets in clouds condense onto the mesh and are funneled to the ground. The water pressure from the descending stream of droplets can then be used to power a generator and create electricity.

Kazantsev reported that the prototype Air HES was able to create approximately 5 liters of fresh water per hour from low level clouds. If the technology scales successfully, it could provide not only portable clean electricity generation but also potable water to inaccessible and/or undeveloped regions where both are sorely needed.

Technology and the need for electrical power have inarguably propelled us into this water scarcity and climate change challenge, but with ingenuity and willpower, technology may well help us out of it as well.