- July 30, 2014

- Posted by: BlueSkies

- Categories: Extreme Weather, Forensic Meteorology

Typically, forensic meteorology is applied to weather events a few years old at most – Did damaging hail really strike that commercial facility in April of last year? Was it a tornado or a microburst that ripped off roofs and uprooted trees last week? Did a lightning strike start that house fire a few months back?

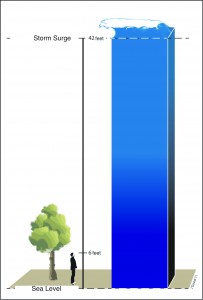

Occasionally, though, forensic meteorologists look decades or even centuries into the past. Such has been the case with Tropical Cyclone (TC) Mahina, which struck Bathurst Bay, Australia, on 5 March 1899 as a Category 5 storm. Since the publication of a research paper by H.E. Whittingham in 1958 titled “The Bathurst Bay Hurricane and associated storm surge” reported that TC Mahina produced a storm surge of 13 meters (or over 42 feet), that storm has generally been credited with the largest ever-recorded storm surge.

Contemporary accounts of the storm reported a waist-deep wall of water inundating a 40 ft tall ridge where several law enforcement officers were camped during the storm, dolphins being found stranded atop 15 m high cliffs after the storm had passed, and fragments of Aboriginal canoes being deposited 70 to 80 feet above the normal high tide.

TC Mahina was a undoubtedly a monster storm. With sustained winds of over 175 mph, it sank 54 ships (mostly pearling vessels) and killed more than 300 people, sweeping devastation across the Bathurst Bay region of northeastern Australia.

Yet despite its impressive statistics and a number of contemporary (albeit generally third-person) accounts of storm-related inundation, meteorologists have long regarded the 13 m storm surge record skeptically. It just didn’t seem possible. The commonly reported central pressure of 27 inches of mercury (914 mb), while extremely low, just doesn’t support a storm surge as high as a four-story building.

Previous studies that used computer models to estimate storm surge given the most likely track and intensity of the cyclone over this topographically complex region had come up well short of 13 m, and field work in the region had not found evidence of debris deposits to the reported 13 m height.

Something was amiss – either the central pressure was lower than 27 inHg or the storm surge wasn’t actually 13 m high. Possibly both.

Despite the contradictory evidence, little research had been done to set the record straight, until recently. In the May 2014 issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS), several Australian scientists revealed the results of their forensic analysis of TC Mahina’s storm surge.

In that analysis, they utilized methods that forensic meteorologists often use to evaluate much more recent weather events: they investigated historical records, examined the physical evidence, and modeled the event. What they learned is that, as is often the case, the devil is in the details.

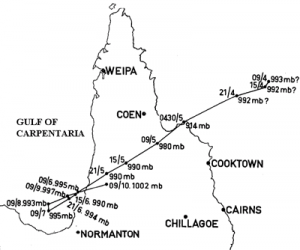

Previous modeling studies had relied upon a thirdhand account of Mahina’s central pressure published in an anonymously authored report several months after the cyclone made landfall. That central pressure – 27 inches of mercury (or 917 mb) – was simply too high to produce a 42 foot storm surge.

By combing through the historical record, though, the authors of the May 2014 study found several references to the storm’s central pressure as an astonishing 26 inHg (880 mb). All of those accounts ultimately were traceable to the same man – a ship captain whose schooner was the only vessel to experience – and survive – the eye of the cyclone. That captain, William Field Porter, also happened to write a letter to his parents recounting his harrowing experience. In it, he stated plainly that “the barometer was down to 26 [inches of mercury].”

So it would seem that the central pressure that had been used in previous modeling studies – studies that had failed to reproduce anything nearing a 13 m storm surge – had been too high. Perhaps the lower pressure of 26 inHg would create the reported record storm surge?

Before jumping straight into the modeling, though, the authors also re-examined the physical evidence – debris that was washed up and deposited by the storm. They found wave-deposited sandy sediments 6.6 meters above mean sea level at Ninian Bay, the location where law enforcement officers reported the 13 m storm surge, but they found no evidence of inundation above that.

This doesn’t necessarily rule out the 13 m water level, however. During tropical cyclones, the highest debris tends to consist of biological material that floats, like leaves, sea grasses, and small marine animals. This material also tends to biodegrade after a few years or decades, leaving no trace for forensic meteorologists peering 115 years into the past. Observations after more recent tropical cyclones suggest that sandy sediments can be deposited at only half the height of maximum inundation, so it is quite possible that the water did reach a height of 13 m above mean sea level at Ninian Bay, where those sandy deposits were found at 6.6 m.

Once the authors had concluded that there was a decent probability that the storm’s central pressure really was 26 inHg and that the waves at Ninian Bay really did reach 13 m above mean sea level, they set about to model the storm surge based on a range of storm forward speeds and storm tracks suggested by ships’ wind and pressure recordings as well as damage assessments after the storm passed.

What they discovered was that even in a worst-case scenario (Mahina approached Bathurst Bay from the northeast with a central pressure of 26 inHg), the storm surge would “only” be about 9 m.

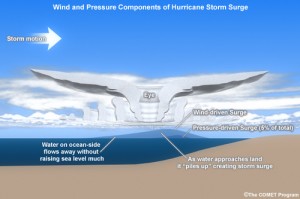

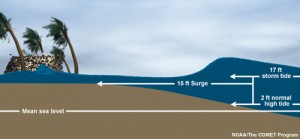

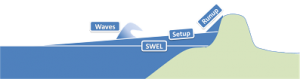

And here is where the devil is in the details. You see, there’s a difference between storm surge and maximum inundation. Storm surge is the abnormal rise of water generated by a tropical cyclone, over and above the natural (astronomical) tides. Click here for an animation of storm surge in an area of steep topography, similar to Bathurst Bay. Storm surge is influenced by the size of the storm, winds speed within the storm, the forward speed of the storm as it approaches land, the angle of approach to the coast, the topography of the sea floor and coast, and the storm’s central pressure.

Maximum inundation, on the other hand, is just what it sounds like – the maximum height that water reaches above mean sea level. Maximum inundation is influenced by the height of the storm surge, the timing of astronomical tides, and various types of wave action like wave setup and wave run-up. It’s the high water mark.

And the high water mark is almost always higher than the storm surge. In fact, in severe tropical cyclones in northeastern Australia, wave and tidal effects have added approximately 25% to the height of maximum inundation.

What this means for Tropical Cyclone Mahina is that the 1899 accounts of a monster cyclone that brought the sea to the top of a 40 ft high cliff may in fact have been accurate. If the central pressure was actually 26 inHg and the storm approached from the northeast, it could have generated a storm surge of up to 9 meters (30 feet). Mahina struck during astronomical high tide, and that combined with wave setup and run-up could have added an additional 4 m (12 feet) of water on top of the storm surge.

So, the record for highest storm surge may have to be revised downward (Mahina’s storm surge was probably 9 meters or less), but its maximum inundation may still take the gold. It is entirely possible that on March 5th, 1899, men waded through seawater atop a 40 ft high cliff and dolphins swam through the tops of 50 ft tall trees.

Blue Skies Meteorological Services offers forensic meteorological analyses of a wide range of weather events — from hail storms to lightning strikes, from flooding to tornadoes, from fog to sun glare. We typically don’t look 115 years into the past, but we’re always up for unique and interesting challenges! Give us a call or send us an email to discuss your weather-impacted legal case, insurance claim, or investigation.